The differences between the rural dweller and one who inhabits the confines of a large urban center are not primarily geographical, nor even political or intellectual. The environment a man finds himself him in is not a neutral medium through which his individual soul is transmitted or refracted according to his particular constitution. Rather, it is an extension of the man's soul, an active, agentic force which works upon his thoughts, opinions, and motivations, much as the baker works upon what will eventually become his boule. In the popular imagination, the city is envisioned as a master sculptor, a Bernini or Rodin who can take the raw material of the rustic and shape him into something ennobled and magnificent. In practice, it is more akin to the forger who attempts to pass off his ineffectual scrapings as great art.

Its products are worse than works in progress; they are victims of an unscrupulous surgeon who promises beauty but delivers its caricature. This is easily seen at the very moment of transition from rural to urban: To orient himself, the bumpkin looks at the people swarming about him, on the sidewalks, in the trains, the markets, seeping out of every crack and enclave in the bustling city. His gaze is met by a people overburdened with worry, disdain, fear, envy. Here he first encounters what Georg Simmel in the "Metropolis and Mental Life" called the "blasé attitude," or mental exhaustion owing to an overstimulation of the sensory system, in particular the visual faculty. The longer he persists in this unseen sea of despondency, the more he comes to see it as man's natural state. His interactions with others quickly shift from personal to transactional, his natural instincts disoriented and ultimately suppressed. If he does not actively adapt himself to his circumstances, he becomes an easy mark; if he does, he is enthralled to the cultural superego Freud describes in "Civilization and Its Discontents," the force which sacrifices the wants and needs of the individual for an uneasy truce among the many in the guise of social harmony.

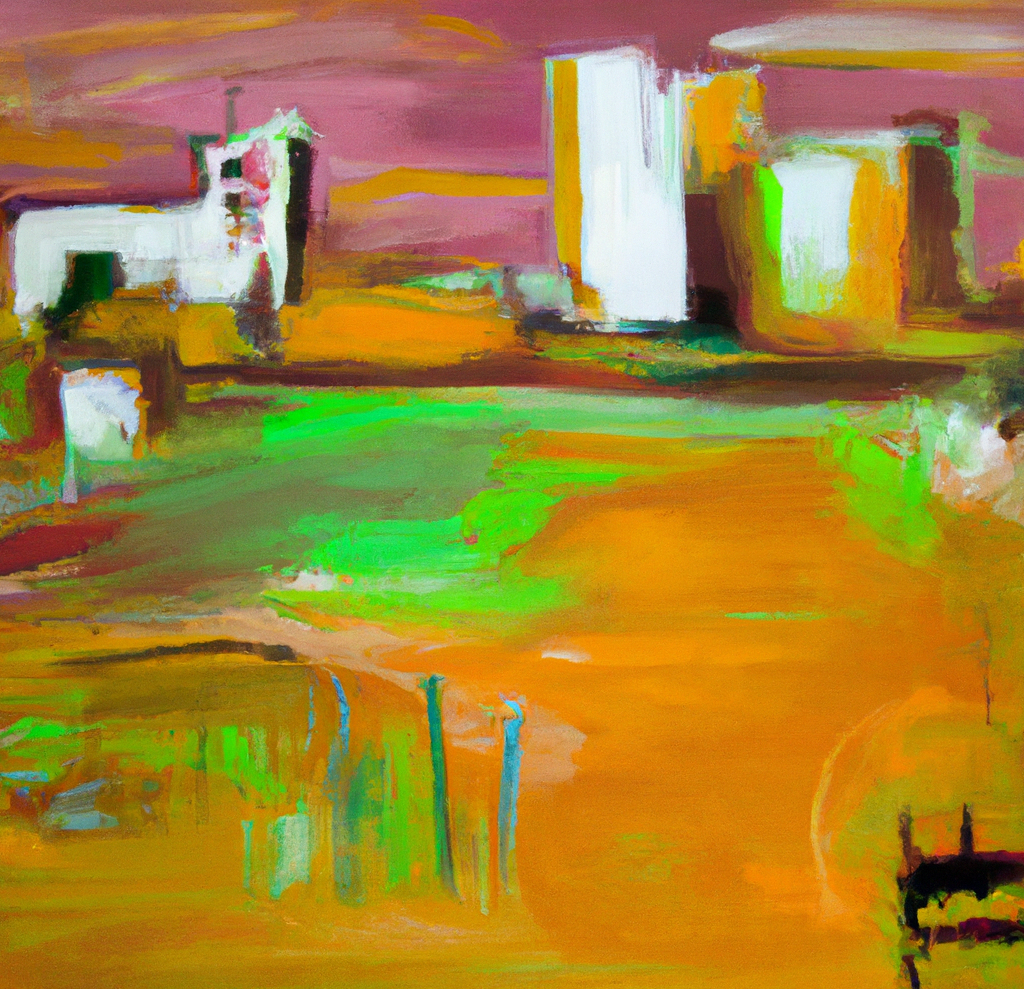

This is not to say that the country dweller is much better off. He, too, is shaped by his environment, but rather than an overabdunace of stimuli, it is a dearth of stimuli which afflicts his soul. None has placed a chisel upon his brow, neither the artist nor the trickster; he is a lump of clay buffeted only by the elements so often found in uninhabited locales: petty prejudices, mistaken notions about the world, a sort of comical insularity. And yet, he remains among the living. His instincts are intact and he may act upon them as he pleases, for good or ill. He is an untapped well of potential and sincerity. Many of his kind will remain as such, untapped, unrealized, unnoticed until they pass in their fifth or sixth decade from some complication brought on by the effluvium of the urban centers.

Is one to be more pitied than the other? Is it better to be among the living condemned to never live, or to suffer a premature death at the hands of the already dead? I venture no opinion on the matter.